Back to list

Back to list

Semiconductor manufacturers are enjoying massive subsidies from China to the U.S. to Europe, but what's the impact?

Source: Nikkei Asia

In mid-June, TSMC urgently dispatched a team to Japan to visit some of the company's equipment suppliers. It wondered, why do these companies say they can't deliver important machines on time? TSMC, the world's largest chipmaker, and its suppliers have been doing their best to deliver on the powerhouse's demands, but this is the first time it has received a message of apology.

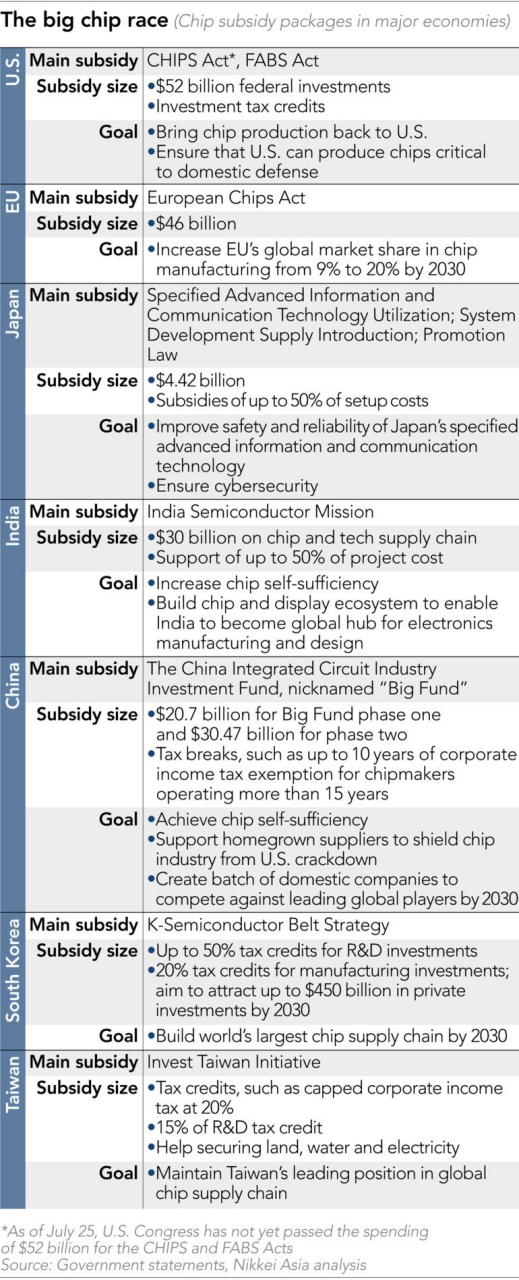

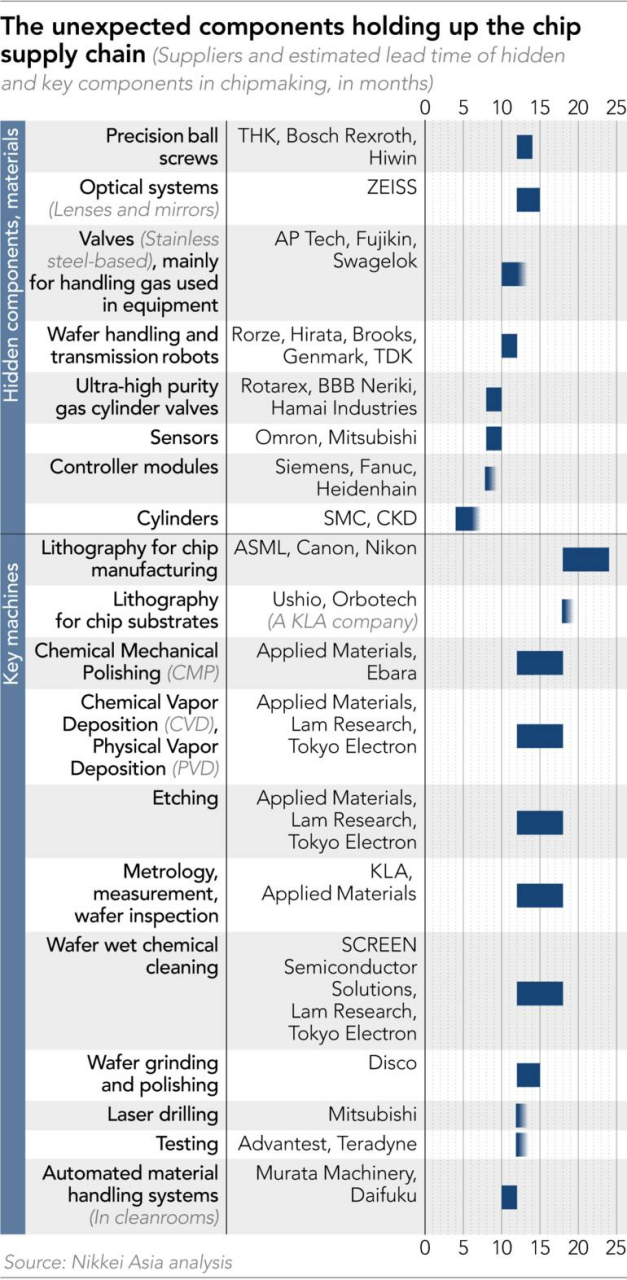

This situation is very sensitive. TSMC is in the midst of a $100 billion expansion, boosted by the government after a severe shortage of key chips last year. But the Taiwanese giant found its supply chain plagued by bottlenecks ranging from lenses precise enough to focus a laser beam on a ping-pong ball on the moon, to seemingly mundane valves and pipes.

Ahead of the June mission, the company's head of supply chain management, JK Lin, and a task force traveled to the U.S. in March for a similar visit to investigate why chip-making machines ordered by TSMC in the U.S. took as long as 18 months to arrive. goods.

And in Japan, suppliers including Tokyo Electron, the country's largest chip-making equipment maker, and Screen Semiconductor Solutions told TSMC they may not even meet their promised extended lead times.

Screen, one of the few companies in the world that makes chemical cleaning machines vital to chip fabs, has a list of obscure components that are difficult to source from its own supply chain. Such as valves, pipes, pumps and containers made of special plastics – all of which are in short supply.

These problems are cropping up from supplier to supplier, making it difficult to solve a global shortage of chips, the heart and brain that power electronics from PCs and smartphones to cars.

These difficulties highlight a host of unpleasant truths, not only for TSMC and its competitors and suppliers, but also for policymakers around the world. Governments in China, the U.S., Europe and elsewhere have decided to "localize" semiconductor manufacturing amid U.S.-China trade tensions and the raging Covid-19 pandemic. So-called supply chain resilience has become a central goal of policy. But this resilience is a "myth".

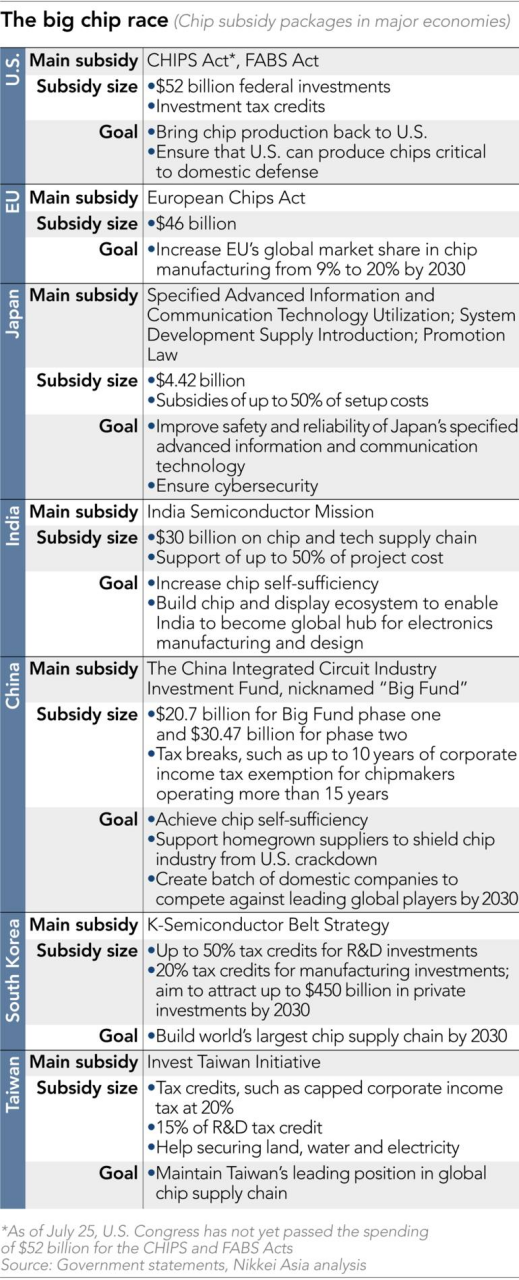

These semiconductor companies receive huge subsidies and state-backed investment aid. The U.S. is expected to vote again on $52 billion in chips. The Japanese government will spend $3.5 billion to support TSMC to build a factory in Japan.

The problem is that these efforts only touch the visible end of the semiconductor supply chain. Behind chip production is a network of supply equipment and other items that include hundreds of raw materials, chemicals, consumables, gases and metals without which the incredibly precise chip-making process cannot function. China has also invested hundreds of millions of RMB to replicate the chip supply chain within its borders.

With only a few specialized suppliers able to meet pollution prevention standards and deal with the red tape of manufacturing projects with potential military applications, increasing capacity is no easy task, especially when supplies of raw materials are limited.

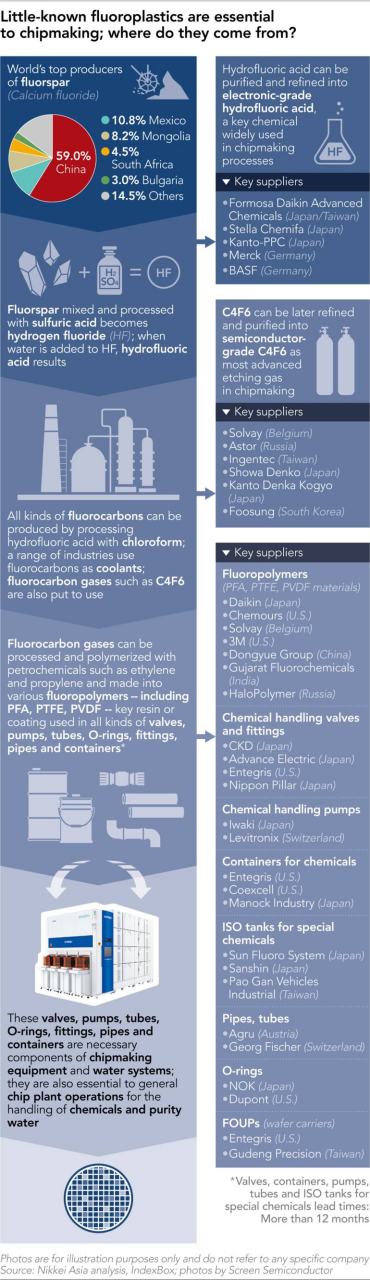

These items are made of special plastics called fluoropolymers, which are essential for handling the caustic chemicals and ultrapure water that flow in all chip fabrication facilities and chip fabrication machines, and the standards are continuing improve.

For example, the state-of-the-art chips used to build the latest iPhone and MacBook processors are now at the 5-nanometer level. Nanoscale refers to the width of lines between transistors on a chip. A nanometer is about 1/100,000 the thickness of a sheet of paper or a human hair. The smaller the nanoscale, the more sophisticated and powerful the chip, and therefore more challenging to develop and produce. Chipmakers, in turn, need to put billions of transistors on a chip. Very low tolerance for defects or micro-contamination.

"The size of a new coronavirus is about 100 nanometers," Kevin Gorman, senior vice president of integrated supply chain transformation at Merck & Co in Germany, told the Nikkei. "That way you know how fine-tuned chip fabrication is and why all the materials are critical."

For semiconductor-grade valves and pipes used to handle chemicals, it is critical that they do not become a source of contamination. And only a few suppliers in the world have the ability to meet the stringent requirements. Japan's CKD, Advance Electric, and American Entegris are qualified valve suppliers; Japan's Iwaki is a major supplier of chemical transfer pumps; industry sources say Agru of Austria and Georg Fischer of Switzerland are important suppliers of key piping systems for chip plants .

Wassenaar Arrangement, a multinational agreement signed by more than 40 countries to avoid shipping such components to certain countries for military use, adds red tape and presents another hurdle for new entrants.

Moving up the supply chain, further obstacles have arisen in the manufacture of fluoropolymers for these components. One such material, called PFA, is only available from Chemours in the US and Daikin Industries in Japan. Its processing requires a lot of technology, and there are no competitors.

Other major manufacturers of fluoropolymer materials include Solvay in Belgium, 3M in the US, Gujarat Fluorochemicals in India and HaloPolymer in Russia. But not all are qualified to manufacture semiconductor-grade materials, and they must supply products for a wide range of industries beyond the tech industry. Material from Russia has been reduced due to disruptions and sanctions caused by the situation in Ukraine.

Hsu Chun-yuan, chief business development officer of TSMC's leading cleanroom maker and rival chipmaker Micron Technology, told the Nikkei that "the sources of fluoropolymers are limited" and "driven by the electric vehicle boom, Demand from both the chip and battery industries is increasing.”

What about going further upstream? Fluoropolymers are processed from fluorite, also known as fluorspar, and China controls nearly 60 percent of global production, according to market research firm IndexBox. China has long identified fluorite as a strategic resource, and in the late 1990s restricted exports due to its importance to industries such as agriculture, electronics and pharmaceuticals, aviation, aerospace and defense. This mineral is often labeled as "semi rare earth".

Mexico is the second-largest fluorite producer, accounting for about 10.8 percent of the market last year, followed by Mongolia and South Africa, according to IndexBox. In Europe, Bulgaria and Spain together control about 5% of the global market. In a supply chain review document released by the White House in 2021, the United States flagged the risk of critical materials at foreign disposal and listed fluorite as one of the "shortage strategies and critical materials" list. The report does not point to its deep ties to the chipmaking industry. It said increasing sources of critical minerals, strengthening inventories and increasing North American manufacturing, processing and recycling capacity could reduce disruption during "future global crises".

Similar problems arise when dealing with gases such as neon for lithography and fluorine C4F6 for etching. Both see Ukraine or Russia as the main source of supplies, which have been disrupted by the war. The professional requirements for the equipment to move these gases are also very high.

The Nikkei Asian Supply Chain survey revealed that only a handful of companies — including Luxembourg’s Rotarex and Japan’s BBB Neriki Valve and Hamai Industries — are qualified to supply ultra-high-purity valves for gas cylinders used in the semiconductor industry. Rotarex controls almost 80% of the market and only produces these specific products in Luxembourg.

Made of stainless steel and other alloys, these valves must undergo multiple verification processes and require government certification due to the risk of leaks and explosions. New entrants need "10 to 20 years" to meet certification standards and testing by different government agencies.

Trade tensions, pandemics and wars

In 2019, the administration of former U.S. President Donald Trump cracked down on Chinese tech champion Huawei Technologies on national security grounds and prevented it from using U.S. technology, especially chips, so demands for the chip supply chain emerged in the U.S.-China tech war. The cry for resilience. The move has spurred aggressive production across industries in China to reduce reliance on the United States and create a secure, self-controlled supply chain.